Ancient Ethics in a Modern Mirror

Introduction

At some point in life, each of us has questioned the soundness of our decisions—whether great or small.

Was I fair?

Was I compassionate enough?

These aren’t passing ethical moments; they reflect a deeper internal struggle between the virtues we claim to uphold.

Thanks for reading Yazeed’s Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.Subscribe

But what does it mean to be “virtuous”?

Are virtues qualities we acquire and follow? Or are they the ability to balance opposing choices?

Can virtues themselves come into conflict?

And if individuals are expected to be virtuous, does society carry a similar responsibility?

Can personal virtue translate into a just political system?

Could our individual failures be the very seeds of societal collapse?

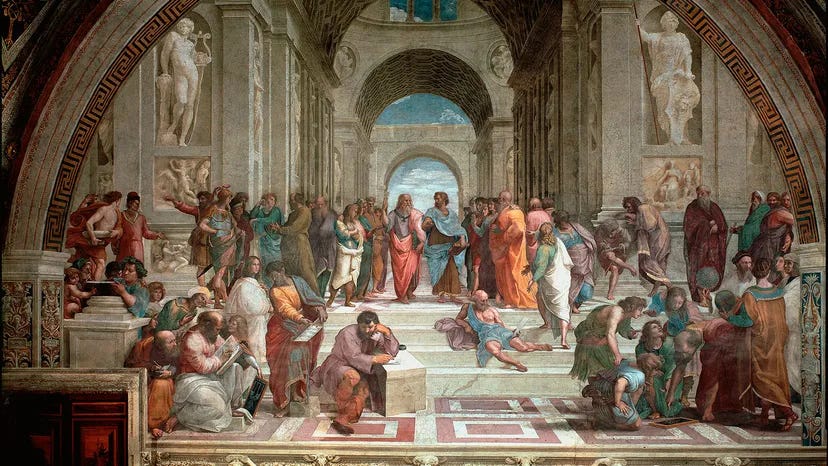

A Glimpse into Plato’s Life

These questions preoccupied Plato—one of the founding figures of Western philosophy—some 2,400 years ago. Born into an aristocratic Athenian family, his philosophical journey began under the guidance of Socrates, whom he saw as the embodiment of virtue. The execution of Socrates, despite Plato’s efforts to save him, became a turning point that shook his spirit and reshaped his thinking.

Viewing the execution as a blatant injustice by Athens’ political system, Plato left the city, spending years traveling to Egypt, Italy, and southern Sicily. He encountered priests, scholars, and scientists, absorbing knowledge in mathematics, geometry, and astronomy—insights that enriched his holistic philosophical vision.

Despite his wide intellectual pursuits, one central question guided his search:

How do we build a just soul—and a just society?

Around 387 BCE, Plato founded the Academy, the first formal institution of higher learning in the Western world, where philosophy, mathematics, and political theory were taught. Among its students was Aristotle, who would later shape centuries of thought.

His writings—mostly in the form of philosophical dialogues—include one of his most influential works: The Republic, where he explored:

- The meaning of justice

- The ideal structure of the state

- The nature of the human soul

- The role of education

- The decay of political systems in the absence of reason

Part I: What Does It Mean to Be Virtuous?

To Plato, virtue isn’t a fleeting behavior or external act. It’s an internal state—a harmony of mind and soul. To be virtuous is to be inwardly ordered and aligned: the rational mind leads, the spirited part (will/emotion) supports it, and the desires obey both.

Plato’s Four Cardinal Virtues:

- Wisdom (Sophia): The ability to think before acting, seeing long-term consequences beyond short-term gain.

- Courage (Andreia): Not the absence of fear, but the will to confront it in defense of what’s right—even when it’s unpopular.

- Temperance (Sophrosyne): A form of self-mastery—conscious control over impulses and desires.

- Justice (Dikaiosyne): Giving each their due and ensuring that every person plays the role best suited to their nature and abilities.

These weren’t just moral traits like honesty or loyalty. Plato chose them for their interdependence—each virtue supports the others in building a “just soul.” There can be no wisdom without the courage to act, no courage without the restraint of temperance, and no lasting virtue without justice to align and integrate them all.

So, are virtues innate or cultivated?

Plato believed virtue is not inborn. It is the fruit of deliberate education and upbringing. Each soul carries a potential for good, but it needs nurturing to grow.

Virtuous Education in Plato’s View:

- Train the mind through philosophy, mathematics, and music to foster order and harmony.

- Refine the emotions through the arts and athletics to help children manage their feelings rather than be ruled by them.

- Shape the environment to favor values like wisdom, courage, and balance—not greed or indulgence.

Without this ethical education, children may grow up either wildly impulsive or blindly obedient—acting virtuous out of fear, not conviction. A child may mistake recklessness for courage or adopt ascetic habits to gain praise, not inner balance.

True virtue is harmony—a union of reason, will, and desire, refined through discipline and insight.

Part II: Can Virtues Ever Conflict?

Despite Plato’s vision of virtue as a unified whole, real-life scenarios often challenge us with moral tensions. Can virtues contradict one another?

Examples of Moral Conflict:

- Justice may demand punishing an employee for a mistake, but compassion (a product of temperance) may hold you back—especially if the circumstances are difficult.

- Courage may urge you to speak out against injustice, but wisdom might suggest the timing or method is unwise.

- Temperance might look like neutrality or passivity, while justice may call for decisive action.

Plato believed the soul has three parts:

- Reason, seeking truth and wisdom

- Spirit, source of ambition and bravery

- Desire, home to impulses and physical needs

When virtues clash, reason—the philosopher-king within—must lead.

Reason doesn’t ignore the heart or the body. Rather, it considers the full context:

- It evaluates consequences, both short- and long-term

- It prioritizes virtues according to situation

- It weighs emotion and logic to choose the most fitting path

Without reason at the helm, moral conflicts may spiral into chaos. A misplaced virtue becomes a vice—courage becomes recklessness, temperance becomes cowardice, justice becomes dogmatism.

Even inaction—failing to decide—can reflect a dangerous imbalance. Plato’s virtues are instruments, but reason is the conductor. Only with its guidance can our moral symphony achieve true harmony.

Part III: From the Inner Soul to the Just Society

Plato believed that a virtuous city is simply a mirror of the virtuous soul. If a well-ordered individual is the model, then a just society must reflect this order in its structure and roles.

He divided society into three classes, mirroring the tripartite soul:

- Philosophers → Govern (like reason)

- Warriors → Protect (like spirit)

- Producers → Provide (like desire)

Virtues in Society:

- Wisdom governs lawmaking and policy

- Courage drives the defense of justice and reform

- Temperance ensures fair distribution and economic restraint

- Justice secures balance—each class fulfills its role without dominance or oppression

Plato called this principle “one person, one function.” A just society thrives when individuals do what they’re best suited for, without overreaching.

Yet, this has drawn criticism.

It resembles a rigid machine, where roles are fixed for life, creativity is stifled, and personal freedom is limited. Plato’s city may be efficient, but by modern standards, it can seem inhuman.

He even suggested that different classes pursue different kinds of “good”:

- Rulers seek wisdom

- Guardians seek honor

- Producers seek wealth

This view flattens human complexity, especially among the working class, as if they were driven only by appetite—with no room for reason or spirit.

Sidebar: Plato’s Theory of Political Corruption

In The Republic, Plato outlines how a virtuous state can fall. Like a soul unbalanced, a state declines when reason loses control, and desire or unchecked spirit takes over.

He describes a sequence of corrupted regimes, each more flawed than the last:

Even in decline, traces of virtue remain—but distorted:

- In timocracy, courage survives but without wisdom

- In oligarchy, discipline masks greed and fear

- In democracy, freedom reigns—but without reason becomes chaos

- In tyranny, all virtues vanish—only raw desire remains

This isn’t just political theory. It’s a moral diagnosis—a blueprint for understanding how a society collapses from within when virtue no longer leads.

Sidebar: The Philosopher-King

Socrates, Plato’s teacher, once said:

“There will be no end to the troubles of states… until philosophers become kings, or kings become true philosophers.”

The ills of the state, he claimed, stem from leadership driven by ambition, greed, or ignorance. The solution? Leaders must love wisdom, not wealth or war.

A philosopher, in Socratic terms:

- Pursues truth, not opinion

- Loves good for its own sake

- Hates lies and loves justice

- Remains unmoved by desires or flattery

- Is patient, curious, and humble

Plato illustrated this with the Allegory of the Cave.

Humanity, he said, is like prisoners in a cave, seeing only shadows on a wall—illusions mistaken for reality. One escapes, suffers the shock of sunlight (truth), and sees the world as it truly is.

But when he returns to free the others, they mock or attack him.

This freed prisoner is the philosopher-king—he who leaves the darkness not to stay in light alone, but to lead others out, even if they resist.

The allegory isn’t just metaphor—it’s a guide to the gap between illusion and insight, between common life and philosophical vision.

Conclusion: A Question That Never Ends

For Plato, virtue isn’t a passing trait—it’s a way of being, a method of aligning the self and the world.

It’s the quiet harmony between what we think, feel, and want—when no part of us drowns out the rest.

But this harmony isn’t constant. Life confronts us with dilemmas—not always between right and wrong, but between two rights.

And in those moments, we’re tested:

- Will reason lead?

- Or will we drift, unexamined?

The health of a society begins with those individual moments. Because for Plato, the state is a magnified soul.

If its parts are out of sync, its justice collapses.

But if well-ordered, justice is made visible.

To be virtuous is not a moral boast—it’s a life project.

One that begins in silence, but echoes through everything we build and live.